For background on section 13 and the justice committee’s online hate study, read this article of mine from earlier in June. To get a sense of how farcical the committee’s antics got during its proceedings, you may wish to read this piece.

After hearing from nearly five dozen witnesses over two months of meetings, the Canadian Parliament’s Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights has tabled its report in the House of Commons.

The report from the Liberal-dominated committee lays out nine recommendations for Members of Parliament to adopt. Most notable is the implementation of a “civil remedy” to combat online hate, which the report acknowledges must first be defined in law.

The Conservatives have already taken aim at the report, charging its recommendations call for an “unacceptable violation” of free speech.

Recommendation 7 of the report:

That the Government of Canada develop a working group comprised of relevant stakeholders to establish a civil remedy for those who assert that their human rights have been violated under the Canadian Human Rights Act, irrespective of whether that violation happens online, in person, or in traditional print format. This remedy could take the form of reinstating the former section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act, or implementing a provision analogous to the previous section 13 within the Canadian Human Rights Act, which accounts for the prevalence of hatred on social media.

Only four of the dozens of witnesses who testified before the committee made preserving and protecting free speech a priority in their remarks, with a majority advocating a restoration of section 13, or a super-charged version of it that holds social media companies culpable for content posted online, as well as the people posting it.

Section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act, repealed during Stephen Harper’s government, allowed for the Canadian human rights commission and tribunal to prosecute online postings, though defendants did not have the same protections or rights afforded to them as those defending themselves in the criminal justice system.

The high standard Canadian criminal law sets for hate speech has caused activists on the left to seek a prosecutorial tool with a lower threshold, prompting the desire for the “civil remedy” sought by the committee’s report.

The report also calls on the government to “establish requirements for online platforms

and Internet service providers with regards to how they monitor and address

incidents of hate speech, and the need to remove all posts that would

constitute online hatred in a timely manner.”

This recommendation is particularly timely, given Canada’s democratic institutions minister, Karina Gould, said last week that the government was not averse to shutting down social media companies who don’t comply with government’s expectations when it comes to political content during the election.

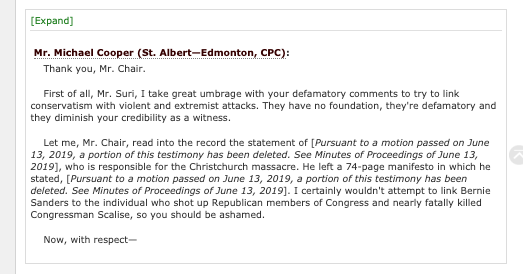

The Conservative members of the committee pushed back against the report, with Conservative MP Michael Barrett arguing these recommendations do “not strike an appropriate balance” between dealing with extremism and protecting free speech.

“Measures like the restoration of section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act are an unacceptable violation of the freedom of speech rights of Canadians,” Barrett said.

Report embedded below:

Taking Action to End Online Hate by Andrew Lawton on Scribd